Why do filmmakers say colour ‘temperature’, and why do you need to shoot at 20,000K near Beta Centauri?

Directors, DPs, colourists and editors, you’ve all at some point asked for a light or a shot to be ‘warmed up’ or ‘cooled down’. But where do we get that language from? Why do we say colour ‘temperature’?

The quick answer (and the intuition that most people probably rely on) is that we associate red with hot, and blue with cold when it comes to taps and air conditioning. Therefore we think of orange light with a lower kelvin value as ‘hot’, and blue light with a higher kelvin value as ‘cold’.

This would explain a surface-level link between temperature and light colour. But as soon as you think about this intuition for more than thirty seconds, it completely falls apart. We use kelvin to measure colour temperature because of something called ‘Absolute Temperature’.

Colour Temperature vs Absolute Temperature

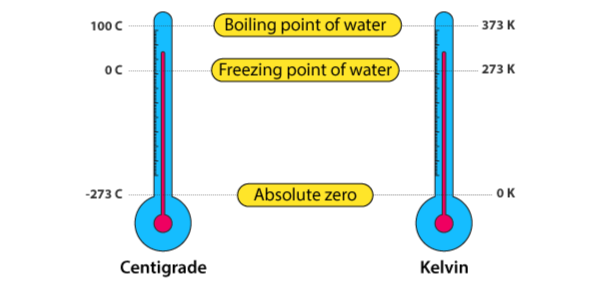

In thermodynamics, absolute temperature is a measure of the kinetic energy in an object’s molecules. If this energy is negligible, the object can be said to have an absolute temperature of 0K. Absolute zero, 0 kelvin, is equivalent to -273 degrees centigrade.

So what does absolute temperature have to do with colour? When we relate this back to the vocabulary we use, it doesn’t make sense? How did filmmakers start referring to higher Kelvin values as colder, and lower Kelvin values as hotter?

Black Body Radiators

When you are adjusting the colour temperature on your film light, you are using a scale that we define using a black body model. It's a theoretical way of understanding the relationship between temperature, and wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation, or colour of light. For the purposes of this video, let’s think of a black body as an object that radiates visible light of a colour proportional to its surface temperature.

If its surface temperature is 1000K, it radiates reddish-orange light, if its surface temperature is 6400K, it radiates white light, and if its surface temperature is 12000K, it radiates pale blue light.

Absolute Temperature and Visible Colour Temperature radiated from a Blackbody (Kelvin)

In real life, stars are a very good approximation of a black body radiator. Our sun has an approximate surface temperature of 5773K, white light, hence we calibrate a camera's white balance to 5600K when shooting in daylight. However, what we are starting to reveal is that the way we think about white balance, and calibrating your camera to the temperature of light it’s seeing, is very conditional to our corner of the galaxy.

Shooting Your Film at Beta Centauri

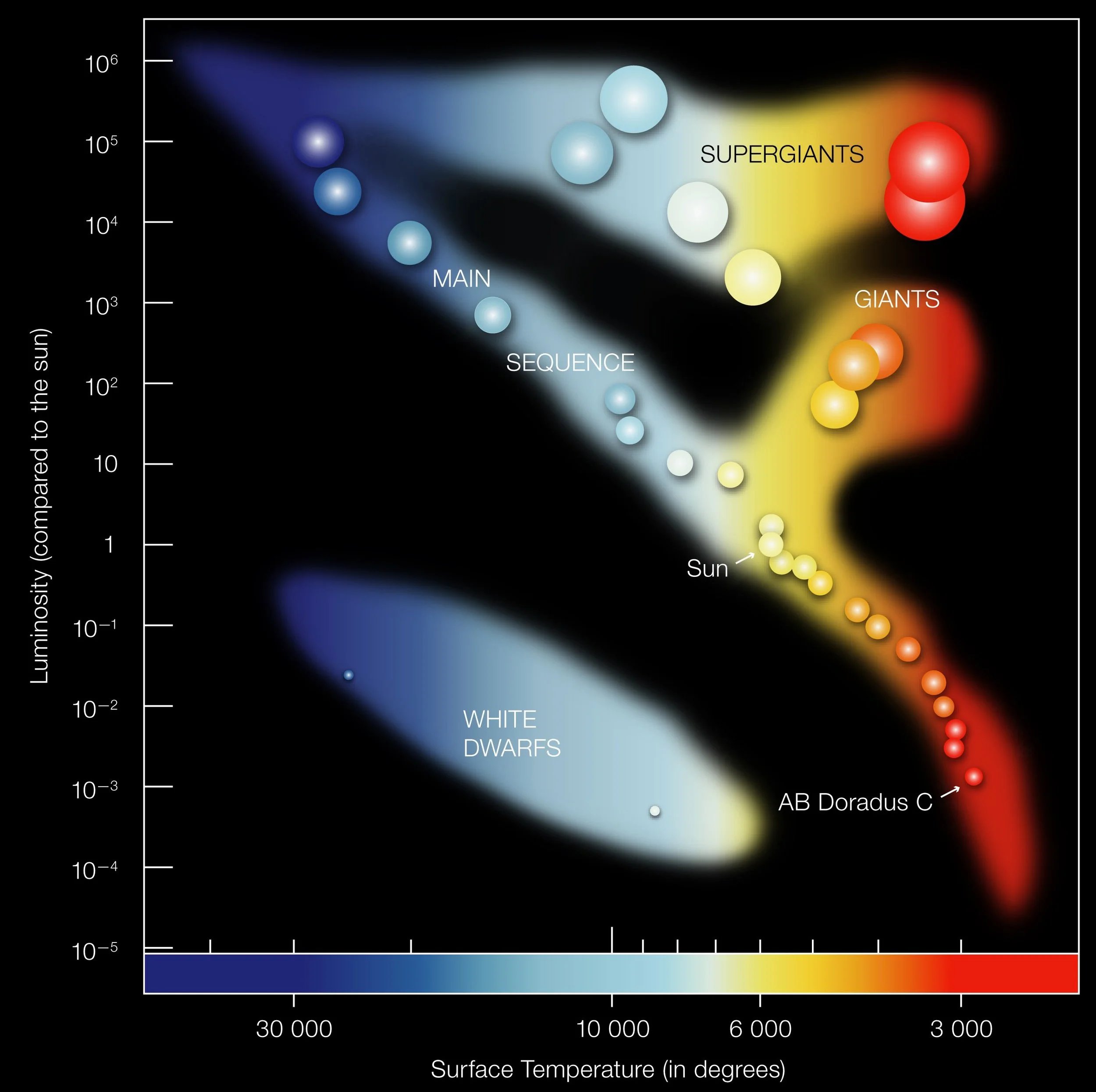

This is a Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. It helps astronomers categorise different stars by luminosity, mass, colour, and surface temperature. What it tells us is that cooler stars with a lower surface temperature of around 3000K are typically orange or red, such as red dwarf Proxima Centauri, or red giant, Arcturus. Hotter stars, with a surface temperature in order of tens of thousands of Kelvins, are blue, such as blue giant Beta Centauri. If you were shooting your daylight scene on the surface of a planet orbiting Beta Centauri, you would need to set your camera’s white balance to around 20,000K.

Artist’s Impression of Blue Giant Star Beta Centauri

Language is Weird

To conclude, what most people say when asking to ‘cool down’ or ‘warm up’ a film light bears no relation to the physics behind colour science or where we get the term ‘colour temperature’ from. It’s a complete contradiction grounded in cultural and historical associations of orange fire with heat, and blue bodies of water or ice with coolness.

The language filmmakers use isn’t going to change, so if it bothers you I’d suggest referring to the Kelvin values when white balancing a light or shot. Please don’t use this blog as an excuse to correct your DoP when they ask you to warm up a light, it won’t end well.